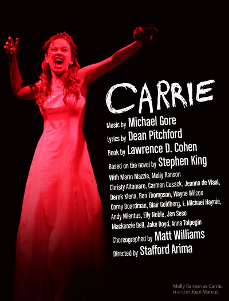

I’ve been obsessed with Carrie: The Musical for much of my life. The ill-fated big budget Broadway adaptation of the Stephen King novel and the Brian De Palma film has perplexed and delighted theater fans for years. The infamous soundboard bootleg from one of the last performances has circulated readily since the late 80s–first on cassette tapes, then CDs, then digital download–and even included demos of the cut songs and interviews about the show. The show is so widely known in theater scenes that, if all the people who swear they saw the Broadway production actually saw it, the show would have lasted more than five performances.

I’ve been obsessed with Carrie: The Musical for much of my life. The ill-fated big budget Broadway adaptation of the Stephen King novel and the Brian De Palma film has perplexed and delighted theater fans for years. The infamous soundboard bootleg from one of the last performances has circulated readily since the late 80s–first on cassette tapes, then CDs, then digital download–and even included demos of the cut songs and interviews about the show. The show is so widely known in theater scenes that, if all the people who swear they saw the Broadway production actually saw it, the show would have lasted more than five performances.

Last year, Carrie: The Musical was revived in NYC. This was the first officially licensed professional production since the failed Broadway mounting. The buzz was huge and the original creative team even came back to revise the book and score. On paper, the show has never been stronger. The new orchestrations are more theatrical than the super-synth/MTV-styled orchestrations of the original. The new songs and lyrics do more to define character and theme than the replaced songs (including my beloved audition song “Heaven”). This is now the official version of Carrie, with a cast recording for sale and everything. It’s really good.

The problem was the infamous Carrie–with all the camp and spectacle–didn’t come with it. The new direction of the show was sincerity and intimacy. The material can handle intimacy, for sure. I dream of a one room adaptation where the entire story is told through the relationship between Carrie and Margaret White with a few moments happening right outside the door: the forced apology, Tommy asking Carrie to the prom, the gym teacher encouraging Carrie to fit in. But camp the story can’t live without. I mean, the revival wanted to do the prom prank scene with a digital projection of blood rather than an actual splash of stage blood onstage. The blood eventually came in but none of the spectacle–the slamming doors, the trap doors, the teenage sexual antics–came with it.

No blood? No deal. Oh, good. They added blood right after this.

One scene from the original production stands out as the embodiment of the potential of Carrie: The Musical. In a scant four and a half minutes, two actors, strong direction, and a brilliant song create such suspense that the audience goes wild.

“And Eve Was Weak” is one of the Margaret and Carrie duets in the show. It happens right after Carrie is humiliated for having her first period in the locker room. Margaret, horrified that her daughter has disobeyed numerous rules, demands Carrie pray for forgiveness. A true Christian worthy of redemption would never receive “the curse of blood” and Carrie has failed her moral duties. Carrie fights back for the first time in her life, demanding an explanation of what she’s actually done and questioning her mother’s take on Christianity.

The two get into a physical altercation onstage. They circle each other and the cellar where Carrie is forced to pray. As Carrie fights back, her mother becomes more frustrated. Margaret drops her daughter down the steps, pushing her deeper and deeper into the hole until she can slam the trap door shut. Then the lights literally burn out in the house and Margaret learns the true meaning of fear.

At its essence, Carrie is a sensationalist show. This stems from King’s own approach to the material. The novel is epistolary, telling the story of a teenager’s murderous rampage through tabloids, news clippings, police reports, school records, and eyewitness accounts of the lives of Margaret and Carrie. The stories told are improbable–rocks falling from the sky, a young girl electrocuting a gym full of people and setting the building on fire, a mother attempting to cast the sin out of her daughter by stabbing her in the bath–but wild enough to make you want to read more.

“And Eve Was Weak,” as staged in the original Broadway mounting, accomplishes that. You can’t believe that this woman is throwing her daughter around for reaching sexual maturity yet it’s happening live in front of you. The daughter, barely able to get off her knees to defend herself, is utterly unprepared for the cruelty of the adult world. Carrie finds a way to fight back, but never finds a way to assert her worth until it is too late. Blowing up the light bulb could have been distraction enough to escape the cellar; instead, she doesn’t find the strength to lash out until she’s already lost the battle. It’s a brilliant visual representation of the power struggle between the characters and functions as narrative-essential spectacle. Who knew an eight foot raked flat could be so horrifying and electrifying?

There is never any doubt that Carrie has powers in the original novel and those powers manifest themselves in increasingly violent ways. You can’t tell this story in shades of gray; it needs the full rainbow of spectacle to breathe and draw the audience in. The first production of this musical to actually focus on the story with the appropriate level of theatricality will be a smash hit. Until then, we have to settle for reconciling the distracting spectacle of the original Broadway production with the subdued but improved exposition of the Off-Broadway revival.

Thoughts on Carrie in any form? Or “And Eve Was Weak” specifically? Share them below. Love to hear from you.

The found footage sub-genre really uses this to great effect. From the unfocused lens of The Blair Witch Project to the social commentary and character study of

The found footage sub-genre really uses this to great effect. From the unfocused lens of The Blair Witch Project to the social commentary and character study of  The opposite can be just as effective. Chuck Palahniuk uses it to great effect in his short story “Guts” from the portmanteau novel Haunted. The novel, a spin on the Amicus-horror film anthology style, has a great set of short stories surrounded by a bizarre framing device. The personal stories of the various participants are more engaging than the story of the artist commune that connects them all, which is the conceit of the novel.

The opposite can be just as effective. Chuck Palahniuk uses it to great effect in his short story “Guts” from the portmanteau novel Haunted. The novel, a spin on the Amicus-horror film anthology style, has a great set of short stories surrounded by a bizarre framing device. The personal stories of the various participants are more engaging than the story of the artist commune that connects them all, which is the conceit of the novel. The obtuse warning is quickly forgotten with all the asides and near-rambling that happens when the narrator diagnoses the world’s problems. Once the narrator breaks the surface of the water for the first time, you know something bad will happen. Then that bad thing gets worse with each paragraph until the result is almost unbearable. The story ends and you can breathe again but the fresh air does not erase the panic from the page.

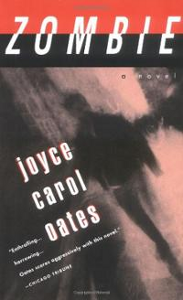

The obtuse warning is quickly forgotten with all the asides and near-rambling that happens when the narrator diagnoses the world’s problems. Once the narrator breaks the surface of the water for the first time, you know something bad will happen. Then that bad thing gets worse with each paragraph until the result is almost unbearable. The story ends and you can breathe again but the fresh air does not erase the panic from the page. The genius of Zombie is Oates’ refusal to pull any punches. You keep reading this novel because you cannot believe that Quentin will go through with his plan. Then he comes up short and starts the exact same plan again. Zombie is relentless in its pursuit of truth in this Dahmer-inspired tale. Quentin will pursue his obsession at any cost and for any small reward he can get out of it.

The genius of Zombie is Oates’ refusal to pull any punches. You keep reading this novel because you cannot believe that Quentin will go through with his plan. Then he comes up short and starts the exact same plan again. Zombie is relentless in its pursuit of truth in this Dahmer-inspired tale. Quentin will pursue his obsession at any cost and for any small reward he can get out of it.