At Quinni-Con 2013, voice actor/director Chris Cason ran a lot of panel about how anime is dubbed and released in the US. He works full time for Funimation, one of my favorite distributors. The panel I was able to catch was all about voice acting from casting to syncing and it was pretty eye-opening.

When Funimation secures a license for a new show, they put together their in-house creative team. As many as seven separate shows are being worked on in different studios at a time with an regular work schedule of 10AM to 6PM. The director is given the translated scripts, character descriptions, and images from the show. However, they’re in charge of researching the show and influences to figure out the crux of the series. They plan for as long as the production schedule allows them so they can figure out the right tone and approach for the translated program.

When Funimation secures a license for a new show, they put together their in-house creative team. As many as seven separate shows are being worked on in different studios at a time with an regular work schedule of 10AM to 6PM. The director is given the translated scripts, character descriptions, and images from the show. However, they’re in charge of researching the show and influences to figure out the crux of the series. They plan for as long as the production schedule allows them so they can figure out the right tone and approach for the translated program.

After research is complete, casting begins. Notebooks are prepared with the title of the show, a description of the show, character descriptions with images, and auditions sides. About 150 people are called in to audition in a mix of scheduled audition slots and cattle calls. The scheduled auditions go off every 15 minutes for three days for a single show.

The voice actors arrive and are instructed to choose three characters they believe they can do the best on the show. They perform the sides and are given direction to see how well they can work with the director. This is a standard tactic in any performance situation. It always freaks my students out when they prepare for an audition and we ask them, on the fly, to go in a different direction. If the director has worked with you before, they probably don’t need to do this part. It’s meant to gauge what the working relationship will be like when the show goes into production.

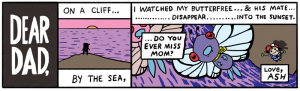

Chris Cason

Once the cast is set and the contracts are signed, it’s time to actually record the show. It’s a much slower process than you would think. Cason says, working one on one with a voice actor, they usually get through 30 scripted lines and 35 reactions–screams, laughs, cries, grunts, etc.–each hour. The sessions with an individual actor usually last three to four hours. It takes about a week to record each episode in an anime series.

Actually directing the show is a challenge. Because of the tight time constraints, the actors are usually working cold. They’re given the script and have to go with it on the day of the recording session.

Once in the booth, the voice actors have to contend with two screens. The script for the show is on the left. The video of the scenes is on the right. We’re not talking about fan parodies on YouTube (that’s another post); the lip flaps have to match for licensed dubbed anime to work. Chris Cason equated it to acting with math. You have to sound good and sync up with a limited amount of time.

Two screens at once for anime dubbing

Once a series has wrapped and the voices are ready to be mixed, it will be months before the cast and creative team can talk about the new show. They sign weighty NDAs threatening bad things if they talk about what they were working on before they’re allowed to. It’s a timing issue with the actual anime license and the distribution deal with the TV network. What it means is that, by the time a new anime dub airs on TV, the cast and creative team have probably recorded another series already that they can’t talk about. It’s a long road from license to release and one that is far more challenging than you might have imagined.

Thoughts on the anime dubbing practice in America? Sound off below.

It is the near future and most crime has been eradicated from Japan. Scientists have discovered a way to accurately measure the probability that someone will commit a crime. This figure is the Crime Coefficient and it is monitored at all times by the Sibyl System. The way to keep a low Crime Coefficient is to receive regular therapy and work on managing your stress levels. Trials and courts are no longer needed as the Sibyl System controls the law, regulation, prevention, treatment, and punishment.

It is the near future and most crime has been eradicated from Japan. Scientists have discovered a way to accurately measure the probability that someone will commit a crime. This figure is the Crime Coefficient and it is monitored at all times by the Sibyl System. The way to keep a low Crime Coefficient is to receive regular therapy and work on managing your stress levels. Trials and courts are no longer needed as the Sibyl System controls the law, regulation, prevention, treatment, and punishment.

Psycho-Pass is the push and pull of modernizing criminal justice. No one is entirely right and wrong in their theories about the role of the Sybil System in law enforcement. There are obvious wrong-doers–murderers, rapists, violent thieves–but they are far out-weighed by what looks like regular people having a bad day. Can you really sentence someone to jail and rehabilitation because they lost their job or got in an argument with a loved one before going outside? And how much of a role does mental health play in determining actual criminal risk? Is a person with anxiety more likely to commit a crime because of their illness than a victim of bullying who is fine so long as he’s nowhere near his abusers?

Psycho-Pass is the push and pull of modernizing criminal justice. No one is entirely right and wrong in their theories about the role of the Sybil System in law enforcement. There are obvious wrong-doers–murderers, rapists, violent thieves–but they are far out-weighed by what looks like regular people having a bad day. Can you really sentence someone to jail and rehabilitation because they lost their job or got in an argument with a loved one before going outside? And how much of a role does mental health play in determining actual criminal risk? Is a person with anxiety more likely to commit a crime because of their illness than a victim of bullying who is fine so long as he’s nowhere near his abusers?

The entryway for the viewer to this twisted world is the relationship between college-aged cousins Kouta and Yuka. Kouta moves to a new beach-front town to attend college. He finds Nyu wandering around the beach during a storm and brings her into his home. Kouta and Yuka quickly befriend Nyu, but Nyu keeps running away. The cousins find out that Nyu is wanted by the police and other organizations and choose to hide her. They don’t even know Lucy exists.

The entryway for the viewer to this twisted world is the relationship between college-aged cousins Kouta and Yuka. Kouta moves to a new beach-front town to attend college. He finds Nyu wandering around the beach during a storm and brings her into his home. Kouta and Yuka quickly befriend Nyu, but Nyu keeps running away. The cousins find out that Nyu is wanted by the police and other organizations and choose to hide her. They don’t even know Lucy exists. Perhaps the strongest aspect of the series is the creature design. These are the shambling zombies of Romero concentrated in a relatively small area filled with desperate people. They don’t have the reasoning skills to turn away from a wall after hitting it, but they’ll stalk you down with terrifying precision if you make a noise.

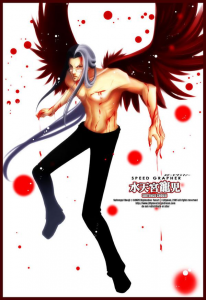

Perhaps the strongest aspect of the series is the creature design. These are the shambling zombies of Romero concentrated in a relatively small area filled with desperate people. They don’t have the reasoning skills to turn away from a wall after hitting it, but they’ll stalk you down with terrifying precision if you make a noise. It’s very perverted, especially for a Shonen series. These are manga/anime titles targeted at boys as young as 10 years old. Shouldn’t the blood and weapon-wielding action be enough to draw in readers and viewers? What is accomplished other than a cheap thrill by drawing action shots like this? One scene in the first episode went on for so long that I thought they were going to show a teenager have an accident caused by fear. It’s a dark mark on a series with a such a strong story.

It’s very perverted, especially for a Shonen series. These are manga/anime titles targeted at boys as young as 10 years old. Shouldn’t the blood and weapon-wielding action be enough to draw in readers and viewers? What is accomplished other than a cheap thrill by drawing action shots like this? One scene in the first episode went on for so long that I thought they were going to show a teenager have an accident caused by fear. It’s a dark mark on a series with a such a strong story.