Yesterday, we took a good look at how Alfred Hitchcock refined the art of cinematic scoring to create suspense in unexpected ways. Today, we’re looking at the complete opposite: silence.

Most films have some kind of scoring. Even if it’s just an opening or closing theme, music is used to establish some kind of frame of reference for the viewer. Young Adult uses a 90s rock song, complete with tape deck and rewind sound effects, to show how the protagonist is trapped in the past. Anna Karenina has an elaborate score timed perfectly with the onscreen action to create a sense of whimsy and melodrama in the story. Original, adapted, or licensed, the origin of the music is not as important as the emotional or contextual reaction to the song.

But what happens when a film doesn’t use any incidental music or scoring at all? In the case of found footage horror and low budget thrillers, it’s a regular occurrence. Having the characters film the action as part of the film cuts the cost of licensing music or hiring a composer/arranger. There wouldn’t be scoring in real life, so why would music suddenly appear in the background in a suspenseful film?

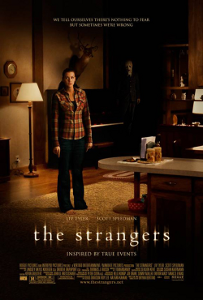

The Strangers is one of the better modern examples of this. The 2008 horror film became a surprise hit because of the unrelenting suspense onscreen. First time writer/director Bryan Bertino took the Hitchcock “bomb under the table” concept to the extreme. The unhappy couple vacationing in the remote cabin have no idea what is going to happen for minutes at a time as we, the audience, see the blood-thirsty strangers circle the house, reach for the phones, and set up their traps. It’s amazing the amount of suspense Bertino got out of one scene where the woman is standing in the hallway completely oblivious to the masked stranger staring right at her through the window for well over a minute.

The Strangers is one of the better modern examples of this. The 2008 horror film became a surprise hit because of the unrelenting suspense onscreen. First time writer/director Bryan Bertino took the Hitchcock “bomb under the table” concept to the extreme. The unhappy couple vacationing in the remote cabin have no idea what is going to happen for minutes at a time as we, the audience, see the blood-thirsty strangers circle the house, reach for the phones, and set up their traps. It’s amazing the amount of suspense Bertino got out of one scene where the woman is standing in the hallway completely oblivious to the masked stranger staring right at her through the window for well over a minute.

More surprising is how The Strangers uses no traditional scoring to advance the mood. There are plenty of opportunities for wistful ballads and fast-paced chase motifs. The camera lingers on a very subdued moment of despair–the woman takes off the ring her boyfriend tried to propose with and sits down at the kitchen table–with no real scoring. A little music here and there could have gilded the lily and really tightened the film up. As it stands, The Strangers was as shocking and effective as it was in theaters because there was nothing in the film to release you from the suspense.

Funny Games, the original and the remake, used the same concept to much better effect. The films establish themselves as otherworldly–first too picturesque and perfect, then too artificial and gameshow-like–so the normal expectations of life and cinema no longer apply. By the time all hell breaks loose and the bad guys force the upper hand, you don’t miss the music. You’re too busy trying to think ahead of the characters onscreen to anticipate the end of the film.

The lack of music in a suspenseful film forces the viewer to pay attention to the screen. It means the screenplay and acting have to be tighter than usual because no amount of edits and special effects will distract from such intense scrutiny of characters and story. It also means that you can get your message across with subtlety and suggestion rather than over the top action set pieces.

The found footage sub-genre really uses this to great effect. From the unfocused lens of The Blair Witch Project to the social commentary and character study of Chronicle, the elimination of incidental scoring in this kind of film lets the story breathe. Sure, you have misfires like Cloverfield where the story doesn’t evolve enough to maintain interest. But you also have shocking successes like The Last Exorcism, where the silence onscreen allows the director and editor to dictate when you get to breathe again.

The found footage sub-genre really uses this to great effect. From the unfocused lens of The Blair Witch Project to the social commentary and character study of Chronicle, the elimination of incidental scoring in this kind of film lets the story breathe. Sure, you have misfires like Cloverfield where the story doesn’t evolve enough to maintain interest. But you also have shocking successes like The Last Exorcism, where the silence onscreen allows the director and editor to dictate when you get to breathe again.

If you want to film a suspense story grounded in real lives rather than over the top spectacle, it’s worth exploring a score-less film. An action-driven story needs the music to guide the mind to the narrative or emotional takeaway of a scene. A dialogue-driven suspense story or even a slice of life gone wrong concept doesn’t necessarily need the extra cross-hairs to align the viewer with the director’s vision.

Thoughts on suspense film scoring or the lack thereof? Share them below.

The opposite can be just as effective. Chuck Palahniuk uses it to great effect in his short story “Guts” from the portmanteau novel Haunted. The novel, a spin on the Amicus-horror film anthology style, has a great set of short stories surrounded by a bizarre framing device. The personal stories of the various participants are more engaging than the story of the artist commune that connects them all, which is the conceit of the novel.

The opposite can be just as effective. Chuck Palahniuk uses it to great effect in his short story “Guts” from the portmanteau novel Haunted. The novel, a spin on the Amicus-horror film anthology style, has a great set of short stories surrounded by a bizarre framing device. The personal stories of the various participants are more engaging than the story of the artist commune that connects them all, which is the conceit of the novel. The obtuse warning is quickly forgotten with all the asides and near-rambling that happens when the narrator diagnoses the world’s problems. Once the narrator breaks the surface of the water for the first time, you know something bad will happen. Then that bad thing gets worse with each paragraph until the result is almost unbearable. The story ends and you can breathe again but the fresh air does not erase the panic from the page.

The obtuse warning is quickly forgotten with all the asides and near-rambling that happens when the narrator diagnoses the world’s problems. Once the narrator breaks the surface of the water for the first time, you know something bad will happen. Then that bad thing gets worse with each paragraph until the result is almost unbearable. The story ends and you can breathe again but the fresh air does not erase the panic from the page. The genius of Zombie is Oates’ refusal to pull any punches. You keep reading this novel because you cannot believe that Quentin will go through with his plan. Then he comes up short and starts the exact same plan again. Zombie is relentless in its pursuit of truth in this Dahmer-inspired tale. Quentin will pursue his obsession at any cost and for any small reward he can get out of it.

The genius of Zombie is Oates’ refusal to pull any punches. You keep reading this novel because you cannot believe that Quentin will go through with his plan. Then he comes up short and starts the exact same plan again. Zombie is relentless in its pursuit of truth in this Dahmer-inspired tale. Quentin will pursue his obsession at any cost and for any small reward he can get out of it.

The problem is that director Sacha Gervasi just doesn’t take it far enough to work. The opening sequence shows Ed Gein kill his brother with a shovel as Alfred Hitchcock addresses the audience ala Alfred Hitchcock Presents. The attack looks like the violence in a Hitchcock film, but lacks the shock or edge of his deft editing. It’s almost like every step is taken to pull back the concept so as to not alienate the audience.

The problem is that director Sacha Gervasi just doesn’t take it far enough to work. The opening sequence shows Ed Gein kill his brother with a shovel as Alfred Hitchcock addresses the audience ala Alfred Hitchcock Presents. The attack looks like the violence in a Hitchcock film, but lacks the shock or edge of his deft editing. It’s almost like every step is taken to pull back the concept so as to not alienate the audience. It’s a shame that the film pulls so many punches as the actors are clearly in on the main gag. Anthony Hopkins and Helen Mirren trade acidic barbs at each for 98 while playing into the exaggerated melodrama of early Hitchcock films. Mirren, especially, sells the Hitchcock Blonde archetype, acting the crap out of a role that starts as eye candy and moves into something much deeper and psychological.

It’s a shame that the film pulls so many punches as the actors are clearly in on the main gag. Anthony Hopkins and Helen Mirren trade acidic barbs at each for 98 while playing into the exaggerated melodrama of early Hitchcock films. Mirren, especially, sells the Hitchcock Blonde archetype, acting the crap out of a role that starts as eye candy and moves into something much deeper and psychological.

The use of music in the film is very smart. Smiley keeps trying to remember exactly what happened at the most recent holiday party for the people in his office. He plays back who talked with who, who shook whose hand, and–ultimately–who went missing with his wife in the bushes behind the office. Instead of hearing a scrap of dialogue, you hear party music. The best is saved for last when the party is shown in full swing to a disco-hued French cover of “Beyond the Sea.”

The use of music in the film is very smart. Smiley keeps trying to remember exactly what happened at the most recent holiday party for the people in his office. He plays back who talked with who, who shook whose hand, and–ultimately–who went missing with his wife in the bushes behind the office. Instead of hearing a scrap of dialogue, you hear party music. The best is saved for last when the party is shown in full swing to a disco-hued French cover of “Beyond the Sea.”