I love a good puzzle game. It’s one of the main genres in my wheelhouse (right behind music/rhythm games and the OCD madness of leveling up and resource distribution in a turn-based RPGs) because of the way I think. I love taking things apart and figuring out how they work.

Puzzle games normally have a breaking point where the learning curve radically shoots up after the basic mechanics are demonstrated. That’s part of the fun. You have to start putting together everything you know to succeed.

Quantum Conundrum has multiple learning curves happening at the same time. The game hinges on the manipulation of physics in a mad scientist’s world. You have very little time to master the intricacies of each of four variables before solving a puzzle demands precision control of various random elements.

Quantum Conundrum has multiple learning curves happening at the same time. The game hinges on the manipulation of physics in a mad scientist’s world. You have very little time to master the intricacies of each of four variables before solving a puzzle demands precision control of various random elements.

You play as a young boy sent to spend some time with your uncle, the brilliant inventor Professor Fitz Quadwrangle. He transported himself to an alternate pocket dimension while testing his latest invention and needs your help to bring him back. Your goal is to start up the generators in the various wings of his mansion to help him return.

To do this, you must use a glove that lets you manipulate gravity and time through dimensional rifts. The Fluffy dimension makes everything super light. The Heavy dimensions makes everything super heavy. The Slow dimension drops everything but your character to one-tenth speed. The Reverse Gravity dimension flips gravity for everything but your character.

Once you get past the first few puzzles, you’ll be manipulating multiple forces at once. You quickly learn things like throwing a big box in Fluffy mode before shifting it to Heavy mode at the last second to smash through a big window or blocking lasers with the appropriate dimensional shift to pass by safely.

What isn’t immediately apparent is how some of the forces link together. Even in some of the later Fluffy/Heavy-only puzzles, the solution to the puzzle isn’t always a logical one. You can block the right laser, but be off by just a slight amount and be stuck for a long time trying to figure out what else you missed. You didn’t miss anything other than the one spot on the wall that the box, held up by a large industrial fan, will line up everything; too bad the graphics already look like you lined it up perfectly even if you’re off by a quarter-width of a box.

The challenge of designing a good puzzle game is deciding where to draw the line between challenge and innovation. Portal, the previous release from Kim Swift (former lead designer at Valve, now with Airtight Games), does a remarkable job of balancing this out.

The challenge of designing a good puzzle game is deciding where to draw the line between challenge and innovation. Portal, the previous release from Kim Swift (former lead designer at Valve, now with Airtight Games), does a remarkable job of balancing this out.

The only thing you’re told in Portal is that you’re a test subject with a gun that shoots portals. Place the orange on one side of an obstacle and the blue on the other and walk through to advance. There are frustrating spots, but only because of the wide variety of possible solutions and the omnipresent element of human error. The game is challenging in the best way possible.

Perhaps Quantum Conundrum‘s biggest challenge is not overly specific level design. It’s rare that you have to do something in just the right order or way to succeed. It could just be that the game guides your hand a bit too much with its training elements so that you expect certain elements to come into play that don’t.

When the techniques you were already taught aren’t relevant to the new puzzle, it’s frustrating. It’s like the moment in a Super Mario game where you first get the new power-up and have no clue what it does. Trading in for the Tanooki suit is great in a precision platforming area, but won’t help too much when the Fire suit would get you past a room full of piranha plants much faster. Some puzzle games introduce new gameplay elements with no explanation again and again as some way of ramping up difficulty.

Puzzle games only have so many ways of creating more challenge to keep a player interested. They can add new gameplay elements, like random enemies or new power-ups. They can expand on the scale of the puzzle, taking you from a single screen of material to a much more sprawling location. They can intentionally leave information out so you have to put the pieces together yourself. And they can also betray your expectations and cause you to break every rule you’ve already been taught to advance.

I love a challenging game. It’s not uncommon for me to spend weeks playing a single title that people can beat in a few hours of gameplay because I want the full experience. You better believe I’m going for all the side quests, meeting all the NPCs to get the full flavor text, or going for the full clear on my first playthrough.

Puzzle games rarely allow for that level of variance. The entire point of the puzzle genre is to solve puzzles. You might couch it in a larger narrative like the Professor Layton series or put in a clear singular throughline like Braid. You can also just make it a series of individual challenges held together by style or character like Tetris or Lumines. You can blend in other gaming elements (music puzzle games like Amplitude or RPG-based puzzle games like Puzzle Quest), but the driving force is clearly the puzzle solving element.

Puzzle games rarely allow for that level of variance. The entire point of the puzzle genre is to solve puzzles. You might couch it in a larger narrative like the Professor Layton series or put in a clear singular throughline like Braid. You can also just make it a series of individual challenges held together by style or character like Tetris or Lumines. You can blend in other gaming elements (music puzzle games like Amplitude or RPG-based puzzle games like Puzzle Quest), but the driving force is clearly the puzzle solving element.

So how do you actually maintain interest in a longer form puzzle game like Quantum Conundrum? It’s honestly a game of chance. People stop playing games all the times for any number of reasons. Puzzle games add on the challenge of taking a singular gameplay conceit–the time reversal of Braid, the black on gray mystery of Limbo, etc.– and expanding it to a full length game.

So many of the popular mobile games are puzzle games because they’re often best enjoyed in small bursts. Could you imagine sitting down for four or five hours at a time to full clear Angry Birds or Cut the Rope? I couldn’t. It might take me a few months to go through all the stages playing a handful of puzzles at a time.

The complications come in when selling a full length, full price console or PC puzzle game. Nowadays, people expect more than the singular action of Tetris or Breakout for the usual console price of $40-plus dollars. Developers add in extra modes or build an elaborate story around a game genre that, until pretty recently, was all about beating stages and levels for a high score.

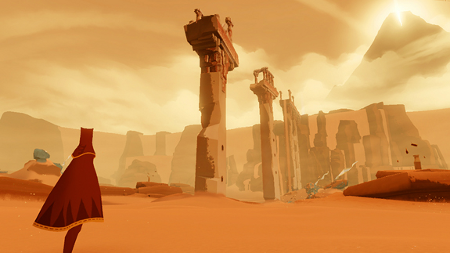

In many ways, these full-length, fully-featured console/PC puzzle games are still an emerging genre. The tricks that worked before–point and click mechanics, especially–don’t necessarily grab interest anymore. Experimental games with puzzle elements (like Journey or Limbo) tend to work best as adventure/platform games with some light puzzle elements rather than puzzle games with some light platforming to get to the next puzzle.

In many ways, these full-length, fully-featured console/PC puzzle games are still an emerging genre. The tricks that worked before–point and click mechanics, especially–don’t necessarily grab interest anymore. Experimental games with puzzle elements (like Journey or Limbo) tend to work best as adventure/platform games with some light puzzle elements rather than puzzle games with some light platforming to get to the next puzzle.

Injecting a traditional narrative into a puzzle game comes down to the story being told. Sometimes, that story isn’t worth dealing with the seemingly random introduction of new gameplay elements just to make the game harder. The line between challenge and obstacle is a fine one. In the puzzle genre (where some gamers are naturally going to be better at certain styles of puzzles than others), that line can be as fine as it is arbitrary.

I haven’t exactly rage quit Quantum Conundrum at this point. I really enjoy my time playing the game. There are just points where the level of frustration created by a particularly inflexible puzzle outweighs the joy of solving the puzzle. I just have to walk away and play something else for a few days.

If the gameplay was the same in each stage, I would get bored and walk away. If it changed radically in style, I would get frustrated and walk away.

If the gameplay was the same in each stage, I would get bored and walk away. If it changed radically in style, I would get frustrated and walk away.

There’s just no way to predict how a gamer will react to a title, puzzle games especially. You can have the best, most inventive conceit to come around in years and fall short because one hard puzzle doesn’t logically flow with the gameplay up to that point. How we respond to games is up to a wide variety of factors that cannot be predicted. I’m not going to be my best at a puzzle game when I have a migraine the same way an arcade fighter fan is going to struggle to adapt to a fighting game that only uses the Wiimote.

The only thing that can be controlled is the actual functionality of the game and story. Do the controls work throughout the game? Does the story make sense and have a logical conclusion? Are there enough hints in the game to at least clue the player into the tools needed for a level? Everything else is up to the gamer’s preferences.

What do you think? Where do you draw the line when it comes to challenging video games? What are some of the puzzle/hybrid games that balance this out well? What game could you just not finish because the whole package didn’t work for you? Sound off with your thoughts below.

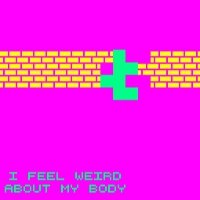

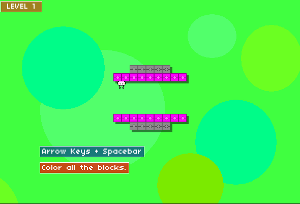

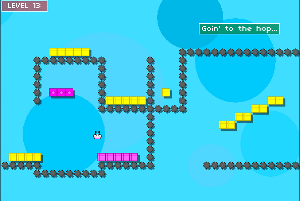

Howmonica is a gravity-based puzzle/platformer that does not want to make your life easy. You control a super cute cupcake-like creature who has to turn all of the boxes in the world pink. You move with the left and right arrow keys and flip gravity with the space bar. It’s all fun and games until the spikes show up and turn your kawaii puzzle game into a living nightmare.

Howmonica is a gravity-based puzzle/platformer that does not want to make your life easy. You control a super cute cupcake-like creature who has to turn all of the boxes in the world pink. You move with the left and right arrow keys and flip gravity with the space bar. It’s all fun and games until the spikes show up and turn your kawaii puzzle game into a living nightmare. Howmonica has a really pleasant looping score and cute sound design that makes the rage-inducing gameplay far more tolerable. You can’t get that mad looking at a cupcake bouncing against a pastel background while turning dull gray squares hot pink. Yet there you are, trying to loop from the top of the screen to the bottom with a one spike gap and hit it just right so you can flip the gravity and land on the last square in the level. It’s a huge challenge.

Howmonica has a really pleasant looping score and cute sound design that makes the rage-inducing gameplay far more tolerable. You can’t get that mad looking at a cupcake bouncing against a pastel background while turning dull gray squares hot pink. Yet there you are, trying to loop from the top of the screen to the bottom with a one spike gap and hit it just right so you can flip the gravity and land on the last square in the level. It’s a huge challenge.

Quantum Conundrum has multiple learning curves happening at the same time. The game hinges on the manipulation of physics in a mad scientist’s world. You have very little time to master the intricacies of each of four variables before solving a puzzle demands precision control of various random elements.

Quantum Conundrum has multiple learning curves happening at the same time. The game hinges on the manipulation of physics in a mad scientist’s world. You have very little time to master the intricacies of each of four variables before solving a puzzle demands precision control of various random elements. The challenge of designing a good puzzle game is deciding where to draw the line between challenge and innovation. Portal, the previous release from Kim Swift (former lead designer at Valve, now with Airtight Games), does a remarkable job of balancing this out.

The challenge of designing a good puzzle game is deciding where to draw the line between challenge and innovation. Portal, the previous release from Kim Swift (former lead designer at Valve, now with Airtight Games), does a remarkable job of balancing this out. Puzzle games rarely allow for that level of variance. The entire point of the puzzle genre is to solve puzzles. You might couch it in a larger narrative like the Professor Layton series or put in a clear singular throughline like Braid. You can also just make it a series of individual challenges held together by style or character like Tetris or Lumines. You can blend in other gaming elements (music puzzle games like Amplitude or RPG-based puzzle games like Puzzle Quest), but the driving force is clearly the puzzle solving element.

Puzzle games rarely allow for that level of variance. The entire point of the puzzle genre is to solve puzzles. You might couch it in a larger narrative like the Professor Layton series or put in a clear singular throughline like Braid. You can also just make it a series of individual challenges held together by style or character like Tetris or Lumines. You can blend in other gaming elements (music puzzle games like Amplitude or RPG-based puzzle games like Puzzle Quest), but the driving force is clearly the puzzle solving element. In many ways, these full-length, fully-featured console/PC puzzle games are still an emerging genre. The tricks that worked before–point and click mechanics, especially–don’t necessarily grab interest anymore. Experimental games with puzzle elements (like Journey or Limbo) tend to work best as adventure/platform games with some light puzzle elements rather than puzzle games with some light platforming to get to the next puzzle.

In many ways, these full-length, fully-featured console/PC puzzle games are still an emerging genre. The tricks that worked before–point and click mechanics, especially–don’t necessarily grab interest anymore. Experimental games with puzzle elements (like Journey or Limbo) tend to work best as adventure/platform games with some light puzzle elements rather than puzzle games with some light platforming to get to the next puzzle. If the gameplay was the same in each stage, I would get bored and walk away. If it changed radically in style, I would get frustrated and walk away.

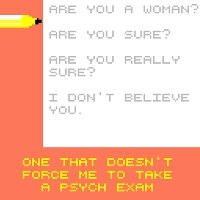

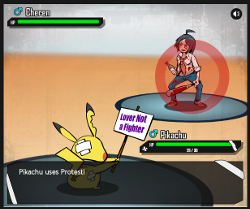

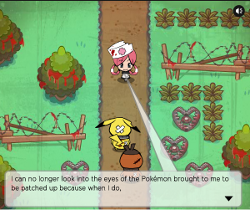

If the gameplay was the same in each stage, I would get bored and walk away. If it changed radically in style, I would get frustrated and walk away. In anticipation of Pokemon Black/White 2, PETA put out a strong satire of the game series to argue their perspective on Pokemon as exploitation. You play as Pikachu escaping from his trainer’s house. You are covered in bandages and not in great shape. Half of your moves are traditional physical attacks; the other half are methods of fighting against animal abuse.

In anticipation of Pokemon Black/White 2, PETA put out a strong satire of the game series to argue their perspective on Pokemon as exploitation. You play as Pikachu escaping from his trainer’s house. You are covered in bandages and not in great shape. Half of your moves are traditional physical attacks; the other half are methods of fighting against animal abuse. It’s not an irrelevant or absurd notion, either. The goal of the game is capturing wild creatures for combat. The only way to catch them is to stalk them in their natural environment and beat them until they’re about to fall over from damage. Your game only stops momentarily when all the Pokemon on your active team can no longer fight.

It’s not an irrelevant or absurd notion, either. The goal of the game is capturing wild creatures for combat. The only way to catch them is to stalk them in their natural environment and beat them until they’re about to fall over from damage. Your game only stops momentarily when all the Pokemon on your active team can no longer fight.